Private Equity Basics

Private Equity BasicsAs the name suggests, Private Equity (PE) is the ownership of privately held companies. Just like in public equities, an investor in Private Equity has an ownership stake or shares in a company. Public equities, however, trade on stock exchanges, like the New York Stock Exchange. These stock exchanges make an active market for the shares of the company and make it far simpler to buy and sell those shares. An investor in a public company can buy or sell their shares at a known price every day that the market is open (weekdays excluding market holidays). Private Equity, on the other hand, is a more disconnected market. Privately owned companies do not have a constantly operating market for investors to buy or sell their shares of the company.

Now that we know that Private Equity is simply the ownership of privately held companies, we can dive into how to invest in the asset class. Since there isn’t an openly active and tradable market for all privately held companies, most people don’t have the ability to buy and sell shares of a privately owned company, much less the knowledge to appropriately price that ownership share of the company. Private Equity firms exist to solve for this need. These firms bring tools and skillsets to the table to enable them to participate in the buying and selling of privately held companies. A good PE firm will have:

Relationships and connections that allow them to see deals (or privately held companies that may be looking to raise capital/sell shares) and other buyers and sellers in the marketplace

Professionals that can appropriately price these privately held companies so that they buy or sell at a price that is acceptable

There’s far more than this that makes a PE firm, but these two areas are critical for successful PE investing and are often outside the scope of the average investor. For this reason, most Private Equity investors make use of Private Equity firms for their PE investments.

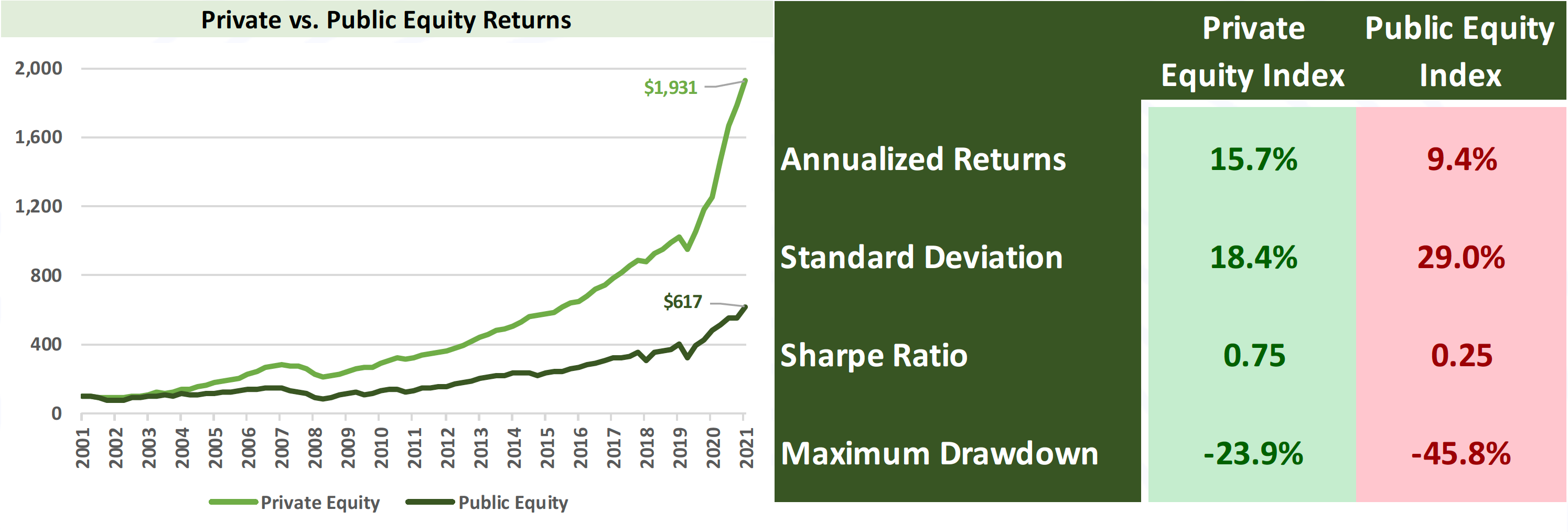

Knowing that Private Equity investments aren’t as easily sold as public investments, an investor may wonder why they should think about adding PE to a portfolio. Fortunately, this lack of liquidity is made up for by the return potential within PE. If we look historically at the returns of Private Equity versus Public Equity, we’re presented a view that is hard to ignore.

Source: Bloomberg, Pitchbook. Data 12/31/2001 – 12/31/2021

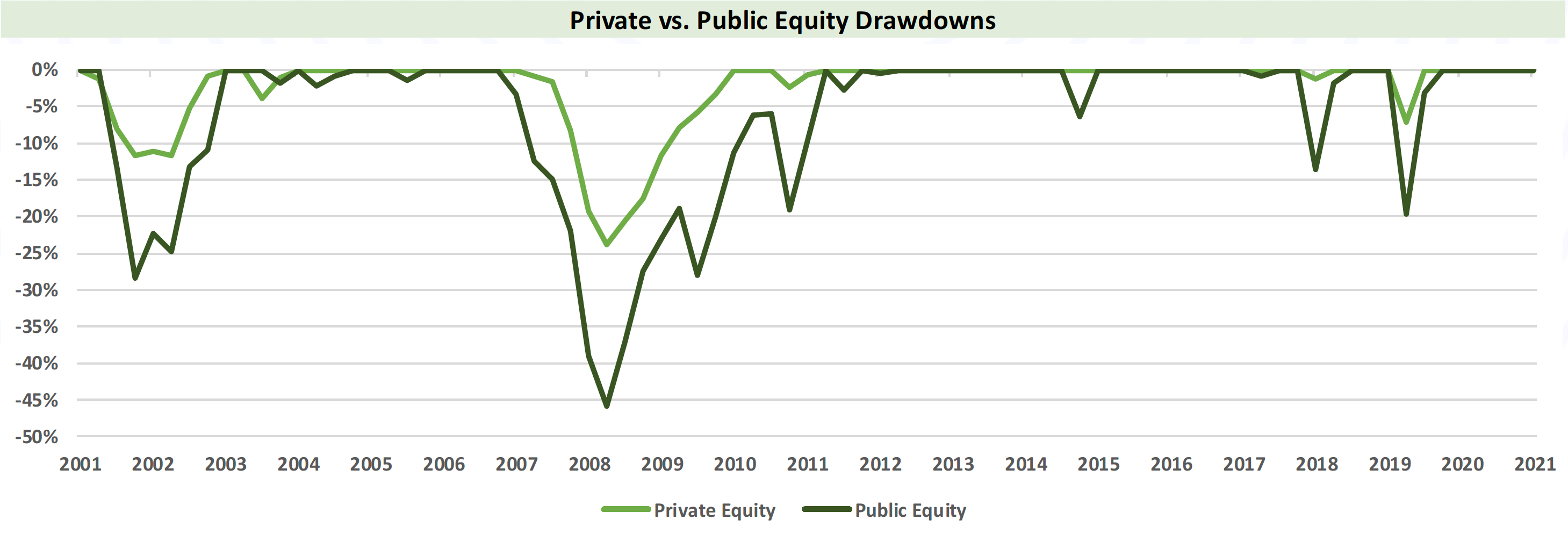

Private Equity over the last 20 years has outperformed public equities by over 6% on an annualized basis. Additionally, when we view the risk of the two investments, we see a significant reduction in the maximum drawdown of PE investments relative to their public counterparts.

Source: Bloomberg, Pitchbook. Data 12/31/2001 – 12/31/2021

The charts paint a picture of an asset class that has historically had more than 1.5x the return potential of public equities, with significantly less volatility. We’ll cover why these discrepancies may exist at a later point, but this data alone tells us that Private Equity is worth consideration.

Venture Capital (VC) is arguably the most notorious of the Private Equity investment styles due in large part to shows like Shark Tank or public success stories like those of early investors in Facebook or Uber. Oftentimes, Venture is broken out as a separate asset class beyond Private Equity. Venture Capital funds allocate to private companies with the ability to grow rapidly and disrupt industries. Venture Capital allows investors to financially back, and own a part of, companies in their early stages. Depending upon where in the company growth stage an investor allocates (Pre-Seed, Seed, Early Stage, Late Stage) that company may be anywhere from a Founder with a great idea, to bridging financing for an IPO. We dissect this asset class more directly in our other educational paper, “Privates School: Venture Capital.”

Growth Equity comes into play at a later stage in a company’s lifecycle than Venture Capital funding. Growth Equity funds require that a company have more established businesses with real revenue, although not necessarily profitable yet. Growth equity funds may track a company and their financials for quarters or years to identify fast growers who may need a next round of fund raising. These investments are typically minority investments intended to align these funds with founders and current management.

Buyout is the largest style within Private Equity and it’s the latest in terms of the company’s lifecycle. Buyout funds seek controlling or majority interests in the company being acquired, which may either already be a private company or a publicly traded company that is being taken private. Current shareholders would cash in on their investments, often financed by leverage taken on by the acquirer. The goal of a Buyout fund is to gain control of the company, make internal adjustments to improve production, processes, and profitability of the company, in order to ultimately achieve a return on the investment.

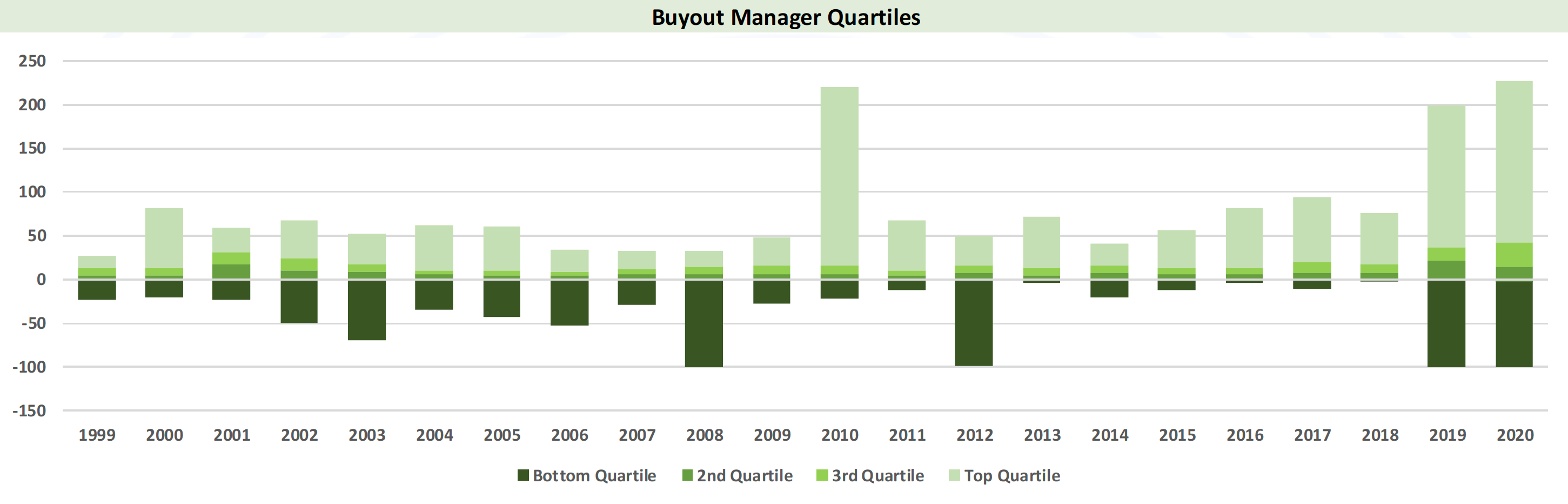

Manager Selection within the Private Equity space is incredibly important. In public equities, one Large Cap Growth fund will look very similar to another. The reason for this is that the universe is nearly identical for these investment vehicles, so they will all own practically all of the same holdings. However, in the private space, funds will have vastly different strategies and holdings. The below chart breaks down the large variabilities in returns and showcases how important it is to select top tier managers, and, most importantly, avoid the bottom quartile managers.

*Source: Bloomberg

Accessing these top tier managers isn’t as easy as it may seem. Everybody wants access to the top managers, so it requires a team capable of identifying who those managers are and then building a longstanding relationship with those managers to ensure that allocation can be granted. In most cases, these managers have more money being handed to them than they can invest, so they’re selective in who they choose to partner with as their investors.

So, what makes these top performing managers better than others? How can a manager successfully build a competitive edge and add value to its portfolio companies? Well, unlike public market investors, Private Equity managers have a number of different tools at their disposal.

Relationships and Deal Sourcing – Private Equity managers use their network to source deals. This provides them access to investments and deals that never make it across a lesser investor’s desk.

Value creation within a Portfolio Company – Once a PE firm has an ownership interest in a company, they do more than act as passive owners. The PE firms will help advise the company in strategic direction and may place employees and management, help with hiring, expense cutting, connect them to additional revenue sources, or source a buyer of the company. The PE group can help take a small growing company to the next level or turn around a failing company.

Leverage – A Private Equity group may help source and provide debt to finance operations. This leverage, if serviced appropriately, can boost returns on their equity investment in that company.

Private Equity funds are typically structured as a limited partnership where the Private Equity Manager is the General Partner (GP), and the investors are the Limited Partners (LP). The GP oversees the day-to-day operations of the fund while the LPs supply most of the capital and are passive investors collecting return on their investments.

While terms will change for different funds, it’s most common to see a 10-year fund life, with an option to extend the life a year or two more. The lifecycle of a fund is fairly straightforward and is made up of three periods.

The fundraising period is the period where the GP seeks out LPs to invest in the fund. The first close is when the first investors commit to investing in the fund. There may be subsequent closes where additional investors commit. Upon final close, no additional investors may enter the fund.

The investment period for the fund usually occurs during the first 2-5 years of the fund and may overlap with the latter parts of the fundraising period. As the name suggests, the GP will be making investments into portfolio companies. During this time, investors will gradually send money to the GP as the investments are made.

The harvest period is when the investments in the portfolio companies are realized. The GP will exit the investments and distribute capital (hopefully gains) to the investors. This process is very gradual. Sometimes an early investment can already harvest gains before the fund is even done making investments. Most exits, however, take longer into the fund’s life. The harvest period lasts until the last of the investments is exited and capital is distributed to the LPs, at which point the fund has completed its lifecycle.

We hope that this Privates School piece has helped shed some light on the world of Private Equity. For those without PE experience, adding this asset class to your portfolio can seem like a risk. However, we have seen that the risks in the asset class have historically been lower than in the public markets. The real question is: Can you afford the risk and opportunity cost of continuing to invest in public market equities, knowing you could easily access their private counterparts through this program.

For a better understanding of exactly where to place this asset within the overall portfolio, please see our A Portfolio Manager’s Guide to Positioning PE Exposure.

For disclosure:

Private Equity: Pitchbook US Private Equity Index

Public Equity: S&P 500 TR Index

Fixed Income: Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond TR Index